Alexandria | Baḥarī

This article is the outcome of “Know your city| Alexandria” Workshop, organized by Tadamun in January 2017, and all the opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of Tadamun.

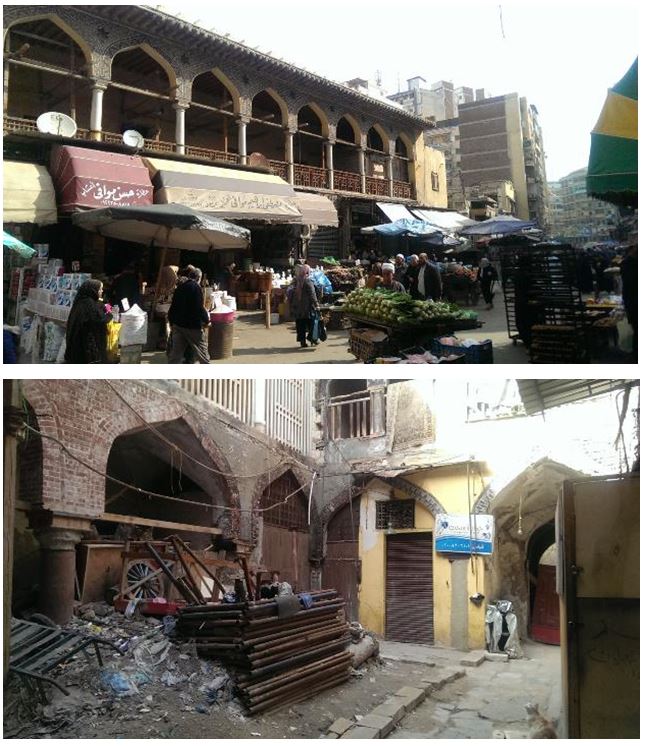

Located in the west of Alexandria and overlooking both the Eastern and Western harbour, Baḥarī is one of the oldest parts of the city and is considered by many to be the “authentic Alexandria”. Narrow winding streets, small two-story houses with jutting upper floors, bazars, okelles1 (wikalah) and workshops along with Sufi mosques are part of what gave this area its unique character(Halim, 2013). However, today, the scene in Alexandria’s oldest quarter is quite different. A significant number of these small houses is either in a derelict condition or has now been replaced with high-rise apartment blocks, putting the area’s infrastructure under severe pressure and posing an unprecedented threat to the city’s historic core. The political turmoil of the last few years is undoubtedly partly, if not mainly, responsible for the demise of this historic area, however, other factors were also involved such as pre-existing notions of the area established long before today. The origins of these most likely go back the early 19th century with the foundation of Modern Alexandria and the focus shifting to the city’s new European quarters.

Baḥarī in numbers

Governorate: Alexandria.

District: al-Gomrok

Area: the total area of al-Gomrok District is 4.7 km2 according to Alexandria Governorate. As to Baḥarī itself, it does not particularly follow any official borders. As defined by some residents, it includes Qaitbey Citadel and Rās el-Tīn palace and extends all the way to Nasr Road and Manshiyya Square with a total area of approximately 2.8 km2.

Population: There are no population statistics for Baḥarī neighborhood, however al-Gomrok District’s population was estimated to be 145,558 in 2008. More recent news sources have estimated that as of 2015, the population has reached 187,000 people.

The Story of Baḥarī

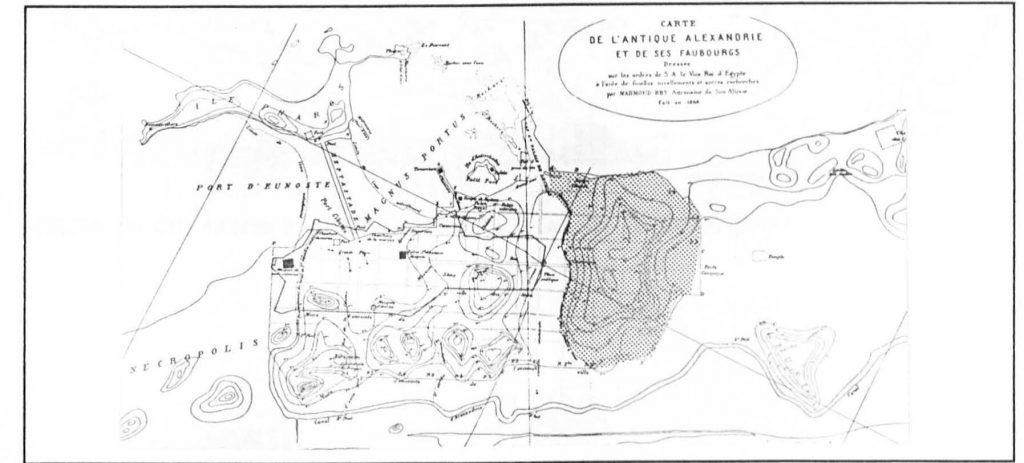

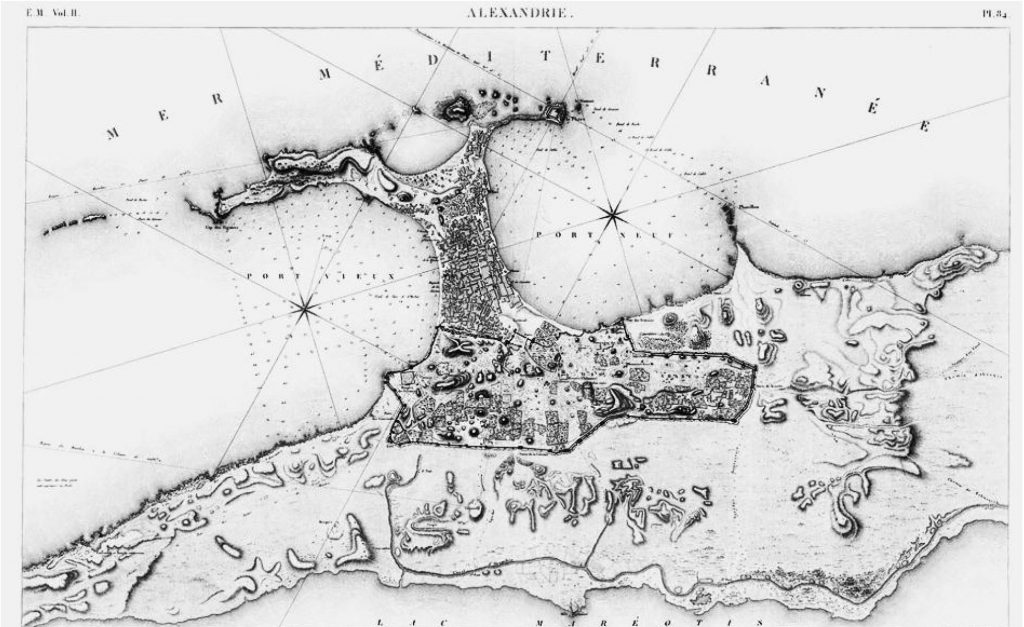

When Alexandria was the centre of the Hellenistic world, the area occupied today by Baḥarī or the Turkish Town was once the Heptastadium, the bridge that connected the mainland to the island of Pharos forming the Eastern and Western Harbours (Hanafi, 1993).2 Alexandria remained Egypt’s capital until the Arab conquest in 641 AD which saw attention shift to a new capital, Fusṭāṭ (modern day Cairo) (Dessouki, 2012). Since the Arab conquest’s interests lay inland, Alexandria was neglected and as such, began its decline (Abdel‐Salam, 1995). Famous British Author Lawrence Durrell saw this conquest as a sign of Alexandria’s impending doom (Fahmy, 2012). As the population decreased, the city walls were rebuilt to enclose a smaller area (Hanafi, 1993). Outside the city walls, a new city developed on the area between the two harbours resulting from silt deposits on the Heptastadium (Ibid).

Figure 2. Map of Ancient Alexandria showing the Heptastadium connecting Pharos to the mainland. (Source: el-Falaky)

In 1517, the Ottoman invasion brought decline once again to Alexandria and as the classical city deteriorated, the city outside the walls continued to develop. In fact, some architectural elements from the classical city were used as structural components in the buildings of this new city resulting in what Awad (2008) calls a hybridization of styles. Built and inhabited mostly by North African and Andalusian immigrants, the fabric of this new city resembled that of many Turkish settlements, with narrow irregular streets, very few open spaces and a dense built environment. This part of the city, known at the time as el-Qasabah (the neck), was the product of the traditional guild with all its building crafts and professions (Awad, 2008). In Alexandria, a History and a Guide, Forster (1986) describes a settlement with small houses and mosques, the architecture of which does not live up to that of the same era.

The discovery of the Cape of Good Hope was a significant blow to the city’s commercial activities (Abdel‐Salam, 1995), and with the Turks deporting skilled workers and imposing high taxes, Alexandria continued to deteriorate and by the beginning of the 19th century, it had diminished to a small fishing village (Dessouki, 2012). This period of time in Alexandria is unfortunately not well-documented, but the available sources describe the city as somewhat disappointing (Hanafi, 1993), at least compared to its ancient venerated past. It was not until the beginning of the 19th century and the appointment of Muhammad Ali as Viceroy of Egypt that the city started to flourish again (Dessouki, 2012). His ambitious plans to revive the once-great city included the construction of a new port and arsenal, the re-digging of the Maḥmūdiyya Canal, the construction of Rās el-Tīn palace and the establishment of a new European quarter to match those in European cities. In order to attract foreign capital, the viceroy granted lands to immigrant communities as well as capitulations. These communities settled in the newly established European quarters and each had an elected president and built its own schools, hospitals and clubs (Haag, 2008). The Turkish Town also continued to develop and expanded towards the area within the old city walls, what is today the area parts of al-Gomrok and al-Manshiyya district. Forster described the Turkish Town as “picturesque and full of gentle charm”(Abdel‐Salam, 1995).

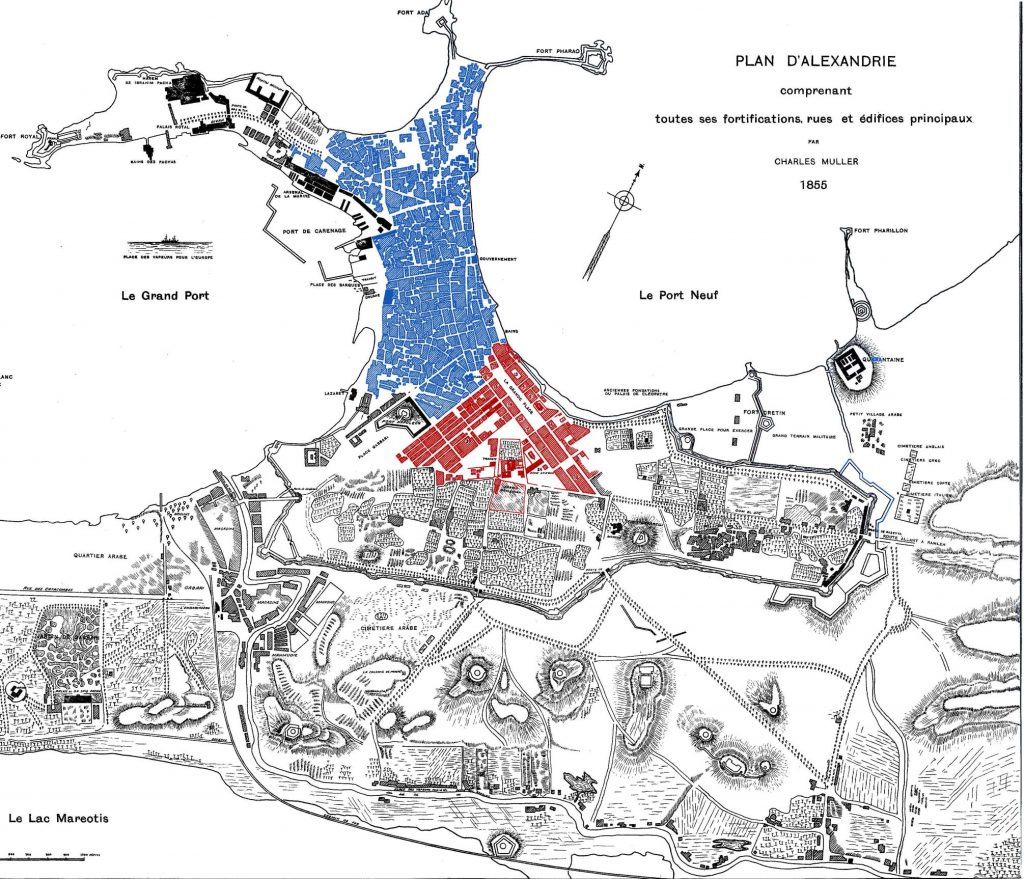

Many accounts describe the city at the time as cosmopolitan in character with the peaceful coexistence of the various religions, classes and ethnicities, Justine, Durrell (1957) describes it as the city of “five races, five languages, a dozen creeds”. However, this, in reality, was not quite the case. Europeans and native Egyptians or ‘Arabs’ as they were called at the time, lived in separate quarters, a marker of a colonial city despite the fact that Alexandria was yet to be one. While the European quarter boasted clean wide streets and new buildings, the Turkish town, where Egyptians lived, was often described as “dirty” with buildings that were old and worn (Reimer, 1993). Furthermore, in 1834, with the establishment of the Conseil de l’Ornato, the focus was on the development and improvement to the European quarters and any intervention undertaken in the Turkish town was for the benefit of the former such as making sure the narrow streets of the latter were clear for the circulation of traffic (Ibid).3

Figure 4. Map showing the segregation between the Turkish Town (in blue) and the European quarter (in red), with Charles Muller’s 1855 map of Alexandria as a base map. (Source: Gustav Jondet, Atlas Historique de la ville et des ports d’Alexandrie, 1921)

Several interventions in Baḥarī followed, such as the establishment of the City Trams (Yellow Trams) in 1897 connecting Ramleh Station to Rās el-Tīn palace as well as the construction of Alexandria’s elegant sea-side promenade (corniche) in the early twentieth century (Awad, 1996). In addition to the corniche, a row of buildings was added on the seafront, which were higher than the Turkish town’s two or three floors and were more influenced by European styles which prevailed at the time (Abdel‐Salam, 1995).

Figure 5. The contrast between the irregular fabric of the Turkish Town and the newer 20th century European development on the corniche. (Source: A.R.E. Department of Survey)

Following the 1952 coup d’état and the ensuing mass exodus of Europeans, newer developments took priority over both the European Quarter and the Turkish quarter. An example of this is the Nasr Road project undertaken in 1957. The project, described by al-Ahram newspaper at the time as “the greatest road in Alexandria’s modern history”, entailed the expropriation and demolition of a 50 meter-wide strip of an early 19th century neighbourhood that is similar to the fabric of the Turkish Town, to make way for al-Nasr Road, thus connecting Manshiyya Square to the western port (Alexandria Municipality, 1959). Not only is there no record of the 100-150-year-old demolished buildings, but a government publication described the demolished neighbourhood as “the dirtiest in the whole city” with old worn- out buildings (Ibid), showing a clear lack of recognition of this historic part of the city. The new buildings added to this road are completely alien to the surrounding fabric in terms of footprint, height and style and do not adhere to what was left of the neighbourhood after the demolition (Said, 2016).

Despite its deterioration over the years, Baḥarī has managed to retain its charm and retains its significant heritage value. Not only does the mix of historic buildings, mosques, okelles, and street markets give this area its unique character, but they are witness to a forgotten era in the history of the city, probably due to the fact that it is associated with a period of decline. Furthermore, since the late 20th century, a wave of nostalgia towards the Belle Époque era, generated—among other things— by the publishing of several literary works such as Miramar (Naguib Mahfouz, 1967), Farewell to Alexandria (Harry Tzalas, 1997), and Out of Egypt (André Aciman, 1994) brought focus once more to Alexandria’s European quarters and the ‘cosmopolitan’ society that used to inhabit them and shifted the attention away from the rest of the city’s historic core, including Baḥarī (Dessouki, 2012).

The People of Baḥarī

News sources’ estimates put the population of al-Gomrok district at 187,000 in 2015, an increase of over 40,000 in just 7 years when compared to official figures in 2008. With the significant number of illegally-constructed high-rise apartment blocks in the last few years, the numbers are likely to be even higher. In fact, according to a 2010 government report issued by the Information and Decision Support Center (IDSC), al-Gomrok district is one of the most densely-populated districts compared to the average density in the city of Alexandria. According to the master plan of the city “Alexandria-2005” published in 1983, 6% of the city’s population lived in that quarter. What is even more alarming is that, in terms of open space for public use, the number of square meters per person is approaching zero (Abdel‐Salam, 1995).

The area was established by immigrant settlers and in the 19th century, it was home to a mix of social classes and ethnicities including Egyptians, Jews, Greeks, Maghrebis and Turco-Circassians, and that is where the different alleys and markets get their name (Halim, 2013). This, however, changed dramatically following the rise of nationalism in the 20th century, which eventually led to the mass exodus of foreigners from all over Egypt..

Today, however, the people of Baḥarī live in relative poverty and work in various fields and industries, with many working as fishermen, or selling fish at the famous Anfūshī fish market or in different crafts, some of which are related to the ship-building industry the area is renowned for. According to one of the residents, many of Baḥarī’s inhabitants choose to work “in the sea”, regardless of their level of education, because it gives them a certain level of freedom that a “normal job” cannot possibly offer. Furthermore, as opposed to many neighborhoods in Alexandria, the community in Baḥarī is also quite self-contained as some of the residents interviewed for this article claim they do not need to leave the area or commute for neither work nor leisure.

Most of the buildings overlooking main streets in the area host commercial activities and in some cases one can find light industry on the ground floor with residential upper floors as opposed to buildings on smaller streets which are, with few exceptions, mostly residential. The area is also known for its markets (souqs), which are mostly street markets selling among other things fruits, vegetables, spices, poultry, and fish. Over the years, there were several failed attempts by the governorate to clear the streets of those markets. While some street vendors stated that they always returned because the government gave them no feasible alternative, others interviewed expressed no interest in moving anywhere else.

Advantages and potential

As the oldest quarter of the modern city, Baḥarī’s potential mostly lies in its heritage assets, both tangible and intangible, as well as its various commercial activities. It attracts a significant numbers of tourists every year, those looking to experience the ‘authentic’ Alexandria. Tourists have a chance to enjoy Alexandria’s unique historic corniche, visit the different historic sites such as the Citadel, Midān el-Masajid, Tirbāna Mosque, Okelle el-Shūrbagy and the various religious shrines that date back to the Ayyubid and Fatimid eras, as well as shop in the area’s different markets and bazars and enjoy a meal at the city’s most famous fish restaurants or in one of its sea-side social clubs.4

Over the years, the area has been an important commercial hub with various markets and bazars, which in some way sustain the bygone legacy of Alexandria as a commercial centre on the Mediterranean. The biggest market in the area is Suq el-Midān, which extends from el-Haggary street all the way to Nasr Road in Manshiyya. The most famous market in the area, frequented by both locals and tourists, is probably Zan’et el-Sitat (women’s market). Other markets include the famous Anfūshī fish market, Suq Libya, a clothes market on Nasr Road, as well as Suq el-`aqadin selling threads, and the jewelry (mainly gold) market on Faransa Street.5

Walking by the sea in Anfūshī, you can see the various ship-building workshops Baḥarī is famous for with craftsmen working on ships and boats of various shapes and sizes. These workshops are frequented by local customers as well as tourists. However, in recent years, according to a workshop owner, the financial and security climate has affected the ship-making industry, especially touristic vessels due to the lack of both funds and demand. Another issue affecting this craft is the fact that so many items are now readymade. Fishing nets which were traditionally handcrafted are now being replaced with the machine-made ones. As such, with the exception of very few old craftsmen in the area, this craft is rapidly disappearing, as the new generation no longer feels the need to learn it.6

Furthermore, various Islamic festivals (Mawālid) are celebrated in the area such as Abū el-‘abbās, el-ʾabaṣīrī, Sīdī Yaqūt and other Sufi figures which attract both tourists and locals. During these celebrations many Baḥarī areas are transformed; streets are decorated, people gather for the festivities, different rides are set up for children to enjoy and a festive atmosphere can be observed all around the area.7

Problems

One of the most critical problems facing Baḥarī is the unprecedented wave of illegal building activity resulting in what some have called “expensive slums”. The area is characterized by its narrow winding streets and small houses, called byūt el-rab’ by the residents. They usually consist of two floors with 4-5 rooms arranged around a small courtyard. Each room accommodates an entire family and each floor shares one bathroom. Unfortunately, the years of neglect have taken a toll on these houses, and the residents are unable to care for them due to the lack of funds and skills. As a result, these houses are being torn down and replaced by high-rise (15-20 floors and sometimes more) apartment blocks. Not only are these new high-rise blocks severely vandalizing Alexandria’s historic skyline with its characteristic minarets, which are no longer visible today, but they are putting unprecedented pressure on Baḥarī’s infrastructure. Instead of the 10-15 families who lived in a small house (byūt el-rab’), an apartment building houses 50 or 60 families, if not more. This has resulted, among other things, in poor street conditions, and overload on the sewage and electricity networks.8

A comparison between the old buildings of the area (left) and new high-rise buildings (right) (Soure: Author)

Figure 9. View of Baḥarī from the Greek Club in 2008. (Source: Rob Leemhuis )

Figure 10. View of Baḥarī in 2013. (Source: Niko Six)

Last December, following a bout of heavy rainfall and bad weather, some areas in al-Gomrok districts were completely flooded due to subsiding street levels and inadequate sanitation networks. Following the outcry of the residents, the governorate and sanitation department drained the water.9 Furthermore, because these new illegal constructions are poorly built and in some cases without appropriate reinforcement or foundations, they have on more than one occasion collapsed claiming the lives of many. However, this is not limited to new constructions, in fact, in Alexandria, Baḥarī comes second in terms of the number of old, derelict buildings, which are currently threatening the lives of approximately 150,000 people. Though there have been some efforts on the part of the governorate to battle this wave of illegal construction and to evacuate and demolish old, derelict old buildings, they have proven to be inadequate, barely a drop in the ocean.

The construction of so many new blocks has led to an increase in the number of inhabitants as well as a dramatic change in the social makeup of the area. When an old house is torn down, the families living there are either given a monetary compensation or promised an apartment in the new block. However, since this new block has more floors and as such can accommodate more than just the families that used to live in the old house, new people, “strangers” [aghrāb] as one of the residents called them, have started moving into the area. This can potentially affect the area’s sense of community. It is worth noting though that rents in old buildings can be as low as 5 EGP due to old rent agreements, whereas purchasing a new apartment in one of these new buildings can be as expensive as 500,000 EGP.10

Residents show two opposing views regarding the new illegal construction. On the one hand, residents who were previously living in old, derelict, small house with other families and who have currently moved into new apartments in the new high-rise blocks after their houses were torn down, do not oppose the illegal constructions; if anything they welcome it as it gave them the opportunity for a better housing situation. It offered them a private home, in a better condition and with better facilities. On the other hand residents still living in shared old houses experience deterioration in their already compromised quality of life, as the illegal constructions have put pressure on infrastructure, and blocked light and air. As such, these residents are completely opposed to these illegally constructed new buildings.

Garbage collection is another issue plaguing the area. Although it is a city-wide problem, some areas in the city such as Baḥarī have it worse than others. According to a resident, it takes weeks of garbage piling up and several outcries from the residents for the garbage to be finally collected by the city. In the ship-building workshops by the shore in Anfūshī, garbage and debris brought about after recent rainfall and high tide has been piling up on the sand and there has been no attempt at collecting them since.

Figure 12. Garbage and debris on the shore in Anfūshī near the ship-building workshops. (Source: Author)

The lack of security in some areas, coupled with the spatial nature of Baḥarī with all its small alleys and streets have made it a favoured place for drug dealers to conduct their business. A well-known example of this is the Jewish Alley (Hāret el yahūd) near Gate 10 of Alexandria’s Western Harbour. Other examples include Hāret bondo’a, Hāret el ba’tariyya, Hāret el-sa`āda, el- mawāzīnī, Hāret Halāwa and Hāret el-Maktab which have all become drug-dealing dens. These areas are perceived as unsafe by outsiders who avoid them at all cost, whereas the residents don’t think of them as particularly ‘dangerous’, but rather as an unwelcome presence, with which they have learned to co-exist for many years.

Interventions

Baḥarī encompasses three conservation areas or parts thereof: the corniche, the Turkish town, and the gardens of Rās el-Tīn. Although all of these areas have specific guidelines on new developments, uses and architectural styles – as part of Alexandria’s historic buildings lists – these are not in any way enforced. In the Turkish town for example which constitutes most of Baḥarī, the maximum allowed height is 1.5 the street width with a maximum of 22 m, the architecture style of the area has to be respected, and harmful industrial and commercial activities should be removed according to the recommendations appended to Alexandria’s historic building lists. Today, high-rise apartment blocks constitute the majority of new buildings, their architectural style completely disregard that of the area, and Baḥarī is overflowing with workshops and markets. These guidelines were proposed with the aim of preserving the unique organic fabric of the Turkish town, however, as they are not enforced, we are currently losing that historic fabric at an alarming pace. The residents spoke of multiple attempts by the governorate to control new building activity and campaigns aiming to demolish illegally-constructed buildings, however, these efforts continue to be inadequate in the face of the fast and intense wave of illegal construction. There are also attempts by the government to improve the rapidly-deteriorating infrastructure with budgets assigned to fix street paving, street lighting as well as some improvements to the sanitation networks (Alexandria Governorate, n.d.).

In terms of interventions in the area, there were some conservation efforts on the part of the government in an attempt to preserve and revitalize some of the area’s historic landmarks, such as Okelle Shūrbagy, Tirbāna mosque and Midān el-Masajid (which includes Abū el-ʿabbās mosque). However, these interventions followed a piecemeal approach that was only concerned with the building and failed to address its physical as well as its socio-economic context. This conservation approach is not new in the area; in the late 19th and early 20th centuries the Comité de Conservation des Monuments de l’Art Arabe chose to inscribe only a few selected mosques in the whole area and not only did it suggest nothing for the surrounding context, but also did not attach any significance to it.11 While at the time, this was a common approach since the field of urban conservation was still in its infancy, today this is not the case. It is also worth noting that this approach in conservation is not a local issue limited to Baḥarī or even Alexandria, but rather a country-wide problem. The recent ‘revitalization’ of Downtown Cairo is a clear example of that.12 Similar cosmetic renovations can be seen on the corniche in Baḥarī, with exterior facades being repainted on the waterfront, neglecting even to repaint the side facades.

The restoration works on both Shūrbagy and Tirbāna are incomplete. Shūrbagy, which consists of a mosque, shops and residential quarters, was evacuated around 6 years ago for the restoration works, but today, both shop tenants and residents have moved back in and while some portions of the building were reconstructed and restored, the building mostly stands in a state of disrepair. A shop owner in Shūrbagy stated that it has been years since any restoration work was undertaken in the building. Tirbāna is in a similar state, and the mosque has yet to be opened despite the desire of the residents to see it open for prayers. Furthermore, according to news sources, the shops below the mosque have also been evacuated almost 6 years ago with no compensations to the shop tenants who were promised that the restoration works would be done in 24 months. However, due to financial issues, the project was halted and the shop owners/tenants are asking for compensation for the period when they were forced to close their shops.

Taking into account the scale of Baḥarī, the interventions undertaken in the area, which mostly followed a top-down approach, were unable to match its rapid pace of development. The situation is further complicated by the fact that new developments in the area completely disregard building laws and regulations which not only represents a safety hazard, but is also a detriment to Baḥarī’s unique character.

Conclusion

Baḥarī is without a doubt one of the most historically and commercially significant quarters in the city of Alexandria. However, this significance is not reflected in the level of care allocated to it. This is probably due to the fact that over the years, many have associated it with a period of the decline in the city’s history, in addition to some orientalist narratives established in the past which saw Baḥarī as nothing more than a ‘charming’ place, but failed to appreciate its historic, architectural, and economic value. Since there was no real attempt at changing them, these narratives are still prevalent today as Baḥarī remains an important tourist destination, with its full potential still untapped.

Most of the interventions undertaken in the area on the part of the government or the governorate were on ad-hoc basis, and offer no long term plans or solutions for the problems the area is facing, the most significant of which is probably the illegal building activity. However, this is a city-wide problem resulting from a combination of factors, such as the lack of political will, an unstable political and security climate and the lack of an appropriate urban extension for the city that accommodates the city’s growing population. These interventions also serve to show an inability to deal with the area’s unique fabric over the years, whether it is on the part of the Comité, the Ornato, the district or the ministry of antiquities. If this is to continue unopposed, not only would it lead to significant ramifications to the area’s already-compromised infrastructure, but the identity and unique character of the area will be lost forever.

Works Cited

Abdel‐Salam, H. (1995). The historical evolution and present morphology of Alexandria, Egypt. Planning Perspectives, 10(2), 173–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665439508725818

Alexandria Governorate. (n.d.). Portal of Alexandria. Retrieved December 2, 2017, from http://www.alexandria.gov.eg/Government/districts/gomrokdistrict/Map.aspx

Alexandria Municipality. (1959). Alexandria Municipality in the era of the Revolution. Alexandria.

Awad, M. (1996). The Metamorphosis of Mansheya. In K. Brown & H. Davis-Taieb (Eds.), Alexandrie en Egypte.

Awad, M. (2008). Italy in Alexandria: influences on the built environment. Alexandria: Alexandria Preservation Trust.

Dessouki, M. (2012). The Interrelationship between Urban Space and Collective Memory. Cairo University, Cairo.

Fahmy, K. (2012). The Essence of Alexandria pt.1. Manifesta Journal, (14), 64–72.

Haag, M. (2008). Vintage Alexandria: photographs of the city, 1860-1960. Cairo ; New York: American University in Cairo Press.

Halim, H. (2013). Alexandrian cosmopolitanism: an archive. Retrieved from http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=_1426698

Hanafi, M. (1993). Development and conservation with special reference to the Turkish Town of Alexandria. (PhD). University of York, York. Retrieved from http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/10921

1. Okelle is the French term for the Arabic wikalah. It refers to a local building type, which was combined with colonial needs for leisure and commerce. While the ground floor was dedicated to commercial activities, the upper floors served as hostels for merchants or for residential uses. Okelles sometimes included a cafe, a theatre and a European post office. Unlike other words such as bungalow and verandah which had their origins in India and entered the common usage of colonizing cultures, the use of okelles remained specific to Alexandrian buildings.

2. The Hellenistic age, in the eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, is the period between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE and the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE.

3. Conseil de l’Ornato is the first modern street and building commission in the Middle East mostly dominated by Europeans and modelled after those in Italian cities. It was responsible for establishing and enforcing building regulations and laying out and naming streets.

4. The Greek club, Yacht Club, Alexandria Shooting club and Pharos club.

5.Author’s interview with a resident that works in the area, 31 Jan 2017

6. Author’s interview with a shop owner, 24 Jan 2017.

7. Author’s interview with a resident that works in the area, 31 Jan 2017

8. Author’s nterview with a resident that works in the area, 31 Jan 2017

9. Author’s interview with a resident that works in the area, 31 Jan 2017.

10. Author’s interview with a shop owner, 24 Jan 2017.

11. Organization established in the 19th century which was responsible for the conservation of Egypt’s Islamic and Coptic monuments and was under the auspices of the ministry of charitable endowments (Awqaf).

12. A major renovation project was undertaken to restore Khedival Cairo to its ‘former glory’. However, so far this project has only been what many called a ‘facelift’ since these renovations were only cosmetic in nature such as facades repainting, street paving, planting new trees, and have only targeted the exteriors of the buildings without even following proper procedures, while interiors and infrastructure are left to deteriorate. The project also called for the removal and relocation of street vendors and coffee shops, changing the spirit of the once-buzzing downtown. Furthermore, these renovations have attracted investments targeting a more affluent population than that of the downtown. Over the years, the project has been heavily criticized due to sustainability and gentrification-related concerns.

Featured Photo by: Hossam Al-Hamlawy, Design by: Tadamun

Comments