Paving the Streets of Mīt `Uqba

Mīt `Uqba is located in the middle of Cairo’s upscale Muhandisīn district, directly overlooking the 26th of July Axis—one of the most important traffic corridors in Greater Cairo. Despite its strategic location, Mīt `Uqba does not receive the same level of government attention or public services of its wealthier neighbors because it is considered a “popular neighborhood.” The lack of services is evident in the physical state of neighborhood’s streets. The sewer system suffers from constant obstructions, often flooding the streets, causing damage to the paving and creating daily problems for both automobile and foot traffic. In response to these conditions, members of the “Mīt `Uqba Popular Committee for the Defense of the Revolution” lobbied the Gīza Governorate to improve the neighborhood’s roads with the cooperation of community members.

Despite the importance of paved streets for automotive and pedestrian traffic through the neighborhood and the clear impact it would have on the neighborhood, the most important element of the initiative was the conscious grassroots mobilization by the youth and residents of Mīt `Uqba that led to maximizing the very limited public resources of the `Agūza district. This was attained by channeling these resources into priorities set by the neighborhood residents themselves. Moreover, their efforts did not stop at setting priorities, since the community members participated in every step of the initiative, including community supervision of the implementation process, which itself led to greater efficient use of the district’s public resources.

The Situation Before the Initiative

Like many neighborhoods in Greater Cairo, the poor condition of Mīt `Uqba’s streets is directly linked to the degradation of underground water, sewer, and electrical infrastructure. First, the water and sewage systems are constantly flooding and the streets do not drain well, causing damage to the pavement. Second, the streets are constantly being torn-up to repair or improve the utility infrastructure. When the repairs are finished, the streets are repaved poorly or not repaved at all. In some cases, there can be too much repaving and as the street level rises relative to the surrounding buildings, when the water lines or sewers leak, the water and or waste no longer pools in the street, but flows to lower ground right into people’s homes. In many cases, residents have built barriers or elevated sidewalks around their homes to keep the water out. While we cannot blame the residents for taking these necessary precautions, these ad hoc modifications to the streets further inhibits vehicular and pedestrian traffic.

Unfortunately, the residents of Mīt `Uqba had no means to demand that their local authorities improve their situation. This is typical for most Egyptians, but especially so for residents living in informal areas. There used to be elected Local Popular Councils (LPCs) on the municipal level which were supposed to serve as the people’s representation in the government, but these were disbanded following the 2011 Revolution and have yet to be reinstated. (Even when the LPCs were functioning, they were hardly representative or responsive to the public and were dominated by the ‘Local Administrative Units’ filled with bureaucrats). The Local Administrative Units (the Districts) also had few economic resources and little control of spending in their district. Most of the spending on public services and utilities is done by national-level ministries which have no formal channels of communication with the public. As a result, resources are spent inequitably within the district and in ways that do not serve the needs of the majority of citizens, but the interests of an elite few. Whether due to corruption, incapacity of the government to implement projects, or contempt for informal communities, this is a textbook example of unrepresentative and unresponsive government.

The Idea and its Implementation

The Beginning of the Initiative and its Development

The ‘Mīt `Uqba Popular Committee for the Defense of the Revolution’ – formed at the beginning of the Revolution – when they learned of a project included in a 2008 government plan for installing natural gas connections in the neighborhood. However, according to the story of some community members, one resident had blocked the project because he sold cooking gas cylinders to the community from a nearby warehouse. The Popular Committee initiated a conversation with the government officials to find a solution to the gas seller’s objections and begin installation of the natural gas infrastructure. Their first attempts were met with scorn by the head of the district and the deputy governor, because “these young neighborhood activists,” according to one of the officials, did not represent the citizens and had no right to speak in their name. The Popular Committee members turned to political activism, calling on citizens to join demonstrations and sit-ins in front of the Ministry of Supply and the Governorate headquarters in order to compel the responsible parties to implement their demands. Gradually, the Committee was able to open up routes of communication with government officials. As a result of their efforts, the Committee is now in direct and constant contact with the head of the district and the deputy governor whereby they are able to report the issues of the neighborhood to these officials, who in turn have become more responsive to these problems.

After getting support from the local district, the Popular Committee made numerous attempts to communicate and negotiate with the natural gas company. The company claimed initially that they did not have the requisite maps and permits for work in the neighborhood and also said that the streets were too narrow to complete the project. Undeterred, the Popular Committee was able to obtain the necessary maps in July 2011 through their budding network of government officials. Work subsequently began on the project.

During the installation of the natural gas network there were numerous obstacles that the Popular Committee worked to overcome. For example, the natural gas company refused to begin the work because they did not have an area to store their equipment. The Popular Committee solved this problem by obtaining permission from the district to use a plot of empty land owned by the Authority of Endowments on Sudan Street for this purpose. The Popular Committee continued to keep in daily contact with the natural gas company and to find solutions for the disagreements and obstacles that they faced until work was completed in the first phase of the project in February 2012 (sector 27 according to the divisions of the gas company). However, when the work continued on the second phase (sector 28) of the project, the idea of paving the streets of the area came up.

It is well known that the gas company is obligated to “put things back in their place” when they are finished with their work, meaning restoring or repaving (patching) the streets which had to be torn up. According to one of the Committee members, this causes many problems including corruption. When the company puts things back into their place they charge to repave the entire street, even though the actual work may only be on a small portion of the road which constitutes a clear waste of public funds. Moreover, any future repair work or extension of the gas network would require tearing up of the asphalt streets, once again ruining the condition of the roadways.

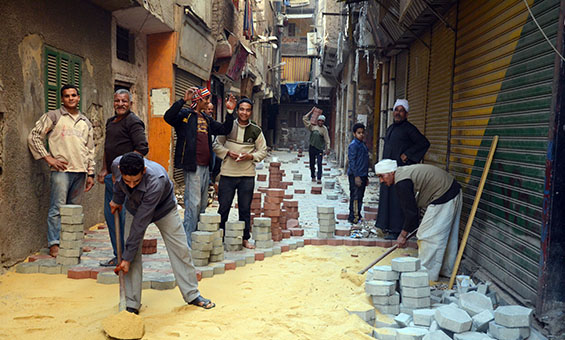

After consulting with several engineers, the Popular Committee suggested the use of public funding available to “put things back in their place” and repave the streets using cement interlocking paving blocks instead of asphalt. They proposed a pilot project to the head of the district to see if the idea would work. They chose `Afīfī Biḥīrī Street and Maḥmud Ḥibaysh Street, the primary entrances to Mīt `Uqba from Wadī al-Nīl Street. A decision on the proposal took nearly a year, as three different district heads succeeded each other. The Popular Committee received approval from the government in the middle of January 2013 to begin work. Due to the efforts and hard work of the initiative the local district also agreed to increase the budget to pave nine streets instead of only two.

Resources and Sources of Funding

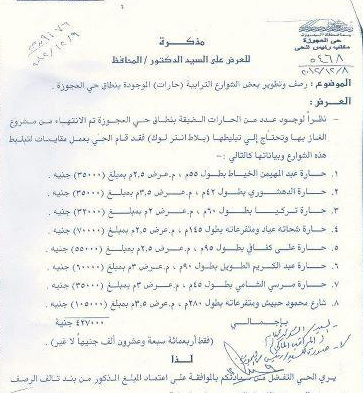

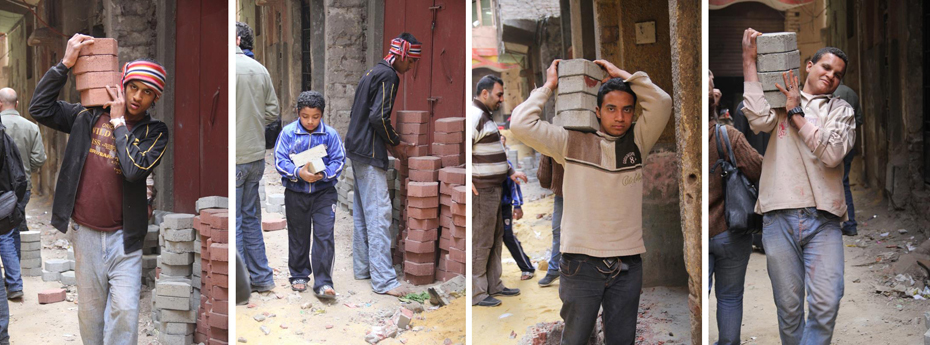

The district provided EGP 427,000 for paving all nine streets. According one member of the Popular Committee, the interlocking paving blocks (EGP 180 per square meter) cost less than the asphalt (EGP 350 per square meter). This proved one of the most important reasons for choosing interlocking paving blocks over asphalt. As a result of the savings, residents were able to pave more streets than they had originally anticipated and had money remaining for other streetscape improvements, such as planting trees. With respect to the human resources, the Popular Committee members expended a great deal of effort in supervising the project and coordinating with the government. The construction efforts were aided by the contributions of sweat equity by community members. Community members also recruited the technical expertise of several engineers who were interested in helping them from the start.

The Popular Committee’s knowledge of the contracted quantities and the budget allocated for paving works enabled them to monitor the implementation of activities. This helped them ensure the quality of the works, as well as the accurate survey of the quantities used. This prevented the manipulation of public funds allocated by the District for these works and insured that these funds were fully utilized for the benefit of the residents and up to the required technical standards.

Assistance and Obstacles

The Popular Committee did not take any aid from NGOs or community service organizations. Although they did receive offers from several political parties and former members of the dissolved National Democratic Party, the Popular Committee refused all such offers categorically, so as not to mire their efforts in politics. Their apolitical stance caused them some amount of harassment. According to the Popular Committee, there was interference from former NDP members as well as the Freedom and Justice Party (the political wing of the Muslim Brotherhood which now heads the Egyptian government). Both parties tried to claim the project as their own in order to advance their political agendas.

The Popular Committee faced several technical issues with the contractor hired to complete the paving. The contractor’s work was shoddy, haphazard, and hastily done. Consequently, the committee members forced the contractor to cease work and reinstall parts that had already been poorly installed.

Another obstacle they faced was the poor condition of the underground electrical and sewer infrastructure. The Popular Committee sought to have these worn out networks repaired before commencing paving, however this was not possible due to inadequate funding. This left the newly paved streets exposed to drainage issues. Fortunately, because the Popular Committee used the interlocking paving blocks instead of asphalt, it will be easier and cheaper to dismantle only part of a road to improve the infrastructure.

Initiative Outcomes and Impact

The Mīt `Uqba paving initiative is an excellent example of local self-management and citizen-government collaboration. The initiative proved the efficacy of community-driven initiatives and the ability of popular committees to supervise projects and manage public resources. The clearest impact of the initiative is the marked improvement of the condition of the streets, making vehicular and pedestrian movement easier. Additionally, the new, enhanced look (and feel) of the streets contributed to the community members’ increased desire to keep them clean, subsequently contracting individuals to clean and collect garbage along the length of the street. Community members have also begun to plant trees and other greenery along the repaved streets. The community involvement in the paving initiative, including those who helped with planning or implementation and those who became involved with the street’s beautification, set a strong precedent for future community work and given the community’s “buy-in,” they will likely have a stronger stake in keeping the streets in good shape. Area residents are very appreciative and grateful to the popular committee for the changes that they implemented in their streets. As for the indirect outcomes, the initiative opened up channels of communication between the community and the government, which helped build mutual confidence and trust. The success of the Popular Committee has encouraged them to propose new ideas to develop the neighborhood and solve future problems.

Sustainability

Social Sustainability

Many of the residents living on the streets that were paved participated in the initiative and assisted with the work. Unfortunately, this enthusiasm was exploited by the contractor who welcomed the assistance of the volunteers to lessen his workload, but did not reduce his fee. In response, the Popular Committee encouraged people not to give up their own labor so easily in light of the contractor’s ungenerous position. Still, the residents’ willingness to participate in the initiative suggests that they will continue to support the area and maintain the improvements that have been made.

Economic Sustainability

The use of the interlocking paving blocks is more economical as compared to asphalt for many reasons. First, in terms of initial cost and cost of repair per square meter, interlocking blocks are substantially cheaper than asphalt. Second, the interlocking blocks are relatively easy to disassemble and reinstall in the event of work on the infrastructure beneath the street, which obviates the need to continually repave streets, neither does it require complex technical skills or resources that the community residents could not directly obtain.

Environmental Sustainability

The decision to choose interlocking paving blocks over asphalt was not merely a passing idea; quite to the contrary, the Popular Committee reached this decision by polling community members and also consulting experienced engineers who provided them with technical assistance. The ability to disassemble and reassemble the paving blocks conserves the materials used for the longest possible period, such reduction in itself being an environmentally sustainable choice for the project as well as maintaining the condition of the streets for as long as possible. It is also worth mentioning that the worn out infrastructure networks themselves were supposed to be changed first before repaving. However this did not happen because of a lack of financial resources. This may cause problems eventually, but due to the flexibility of the interlocking paving blocks, changing out the network and returning the street to its former state would be relatively easy.

Opportunities for Repetition and Future Plans

The members of the Popular Committee are keen on continuing to compel officials to pave the remainder of Mīt `Uqba’s streets with interlocking paving blocks. After the initial nine streets were completed, they successfully lobbied to pave a new street, bringing the total number to ten streets paved as of March 2013. Additionally, the members of the Popular Committee have begun a process of preparing a redevelopment plan for the neighborhood, including plans for planting street trees, installing rooftop gardens, implementing trash collection, and taking measures to beautify the streetscape. The Popular Committee is in negotiations with several initiatives and organizations to participate and provide assistance. Work is scheduled to begin on Maḥmud Ḥibaysh Street as a pilot project. It is worth mentioning that in some of the streets in Mīt `Uqba, residents have begun electing administrative councils for their street in order to represent residents. The administrative council for Maḥmud Ḥibaysh Street has itself agreed on creating a monetary fund to support the implementation of a plan for improving the street.

The experience of the Popular Committee members working with local municipalities over the past two years has been instructive. One member of the Popular Committee suggested amending the municipal law (Law of Local Administration) to activate the role of citizens in urban governance, first, to provide oversight against corruption, and second, to participate in decision making so that public expenditures are aligned with residents’ priorities in each neighborhood. The Popular Committee in Mīt `Uqba is also seeking to connect with initiatives and popular committees working in different neighborhoods to share experiences and work on other similar projects in these neighborhoods.

The members of the Popular Committee want to bring media attention to community-driven experiences and experiments such as their paving initiative. They recognize the power of the media to spread these experiences to the greatest number of citizens, but also to provide a positive picture of the Revolution, its activists, and the work that they do serving their communities. They believe this may push others to benefit and repeat these kinds of projects in other neighborhoods. The Popular Committee has made a number of recordings and interviews regarding the initiative, which are available to watch on YouTube:

“Egypt’s Revolution Continues in Mīt `Uqba”

“The Youth of Mīt `Uqba Fight the Remnants of the Former Regime”

TADAMUN’s Viewpoint

The Mīt `Uqba paving initiative is notably different from a great many other street-paving projects or other similar community-improvement initiatives. Unlike most other initiatives, it was not funded by a corporation or development organization, nor was it a project of the Informal Settlement Development Facility or a local NGO. Rather, it was funded with public resources already available to the district and the governorate. The key was using popular pressure to compel the local government to take on the project. The political activism also opened communication with the government and gave residents continuous oversight of government officials throughout the project. The community was also able to engage professionals who offered their opinion about the feasibility of the interlocking paving blocks, which the community was then able to suggest to the government. Most importantly, this project was not run by top-down decisions from an authority, but rather through a dialogue between the Popular Committee and the government. The asphalt was traded out for interlocking paving blocks after the popular committee was able to compel officials along technical and economic grounds. This alone should be considered a success and a step towards building confidence and making room for the participation of citizens in decision-making related to their needs and everyday lives.

The success of the Mīt `Uqba paving initiative provides valuable lessons for other neighborhoods and districts:

- Opening channels of dialogue and direct communication between neighborhood inhabitants and local administrative officials at the district and governorate level, in order to present residents’ needs and priorities to government bodies is critical. In truth, this was no easy task. Reaching this point took a great deal of effort and pressure, using of a variety of tactics, including direct dialogue, protests, sit-ins, use of media, and leveraging political capital through the community’s political and social networks. The local administrative officials did not welcome this situation in the beginning. It took the patient, persistent efforts of the Popular Committee members to gain the trust and confidence of the government officials. Once this trust was built, however, the officials were responsive to the community and were willing to cooperate with them to achieve their goals. This cooperation ensured that the limited public resources available to the community were used for what residents really needed. This is directly contrary to the traditional mode of operation in Egypt where there is no dialogue between communities and district officials as they undertake public repair work or service provision which might be fine in their own right but do not represent the true needs of the community.

- Citizens must continue to demand their rights and transparency of local and public institutions so that they have access to information and awareness about available resources and local administration plans. The persistent demands of the Popular Committee in pushing for access to information, maps, plans and budgets for the district and governorate were critical to the project’s success. Without such information, the project would have never taken off. Access to information is an essential and natural right for any citizen living in a country that claims it is a democracy, yet in the Egyptian situation, such simple bits of information are treated as state secrets and made difficult to access for ordinary citizens. Access to information about district budgets, plans, and projects are an essential right for every citizen.

- Activating the role of citizen and social oversight over the performance of government officials and contractors is also extremely important. Another reason for the success of the Mīt `Uqba paving project was the direct oversight by residents on all aspects of the project. They knew the size of the budget’s project and the guarantees made by the contractor. They could match this information with the quality and timing of the work done by the contractor and ensure that there was no corruption within their project. Because the first part of the project (the natural gas lines) was in fact planned by the district, the residents had to demand access to this information (see the point above) to provide the necessary oversight. On the second phase of the project, the community members exercised their right to question the district about their means and technical methods during the planning phase and construction. Despite the culture of protest engendered by the Revolution, this kind of open questioning of the government’s technicians is still very rare. This accountability and shared technical insights and expertise among some residents allowed them to propose a new solution that diverted from the original plans of the district and even aided in increasing the scope of the project beyond the original plan.

All of these aforementioned roles are essential components of the elected LPCs, which are supposed to serve as representatives of the people across Egypt. However, even before they were disbanded in 2012, these councils did nothing of the sort. They did not serve as a channel for communication between the government and the general public, they did not share public information such as district budgets and plans with citizens, and they did not perform their duty to oversee the fair public distribution of resources in their jurisdiction. This is due to several reasons: 1) a lack of resources from the government at the municipal level; 2) a lack of equity in the distribution of these resources between different districts; 3) corruption; 4) dominance of the ruling party 5) the LPCs’ inability to hold the government accountable and call for a “no confidence vote” to remove local executive councils; and finally, 6) the absence of legislation that ensures the right of citizens’ to free access to information or policies that give ordinary citizens the right to provide oversight on the local administrative unit’s performance and projects.

The Popular Committee in Mīt `Uqba is characterized by its independence and reliance on volunteer effort. The support of the community came easily to the Committee because they are part of the fabric of the society and not strangers to the neighborhood. Throughout the project, they remained accountable to the community, listening to their needs, and demands. The legitimacy of the Committee was derived through popular support, not through administrative delegation or law. This has many positive aspects, particularly as it makes it easy for them to communicate with people.

However, this role also raises many questions about the continuation of such entities in the near future. Without a doubt such entities will have to develop institutionally and improve their practical expertise in various fields, however, several questions remain.

- What is the regulatory framework that would allow for these committees to play a role as representatives of citizens and as a watchdog over public budgets, plans and performance of local government?

- How can this kind of institution be recognized by the state?

- How will these popular entities remain autonomous, independent, and politically neutral?

- What will be their role when elected LPCs are reinstated through the next round of elections?

We must collectively study initiatives such as this one in depth and look to similar examples and experiences in countries like us that achieved significant progress in this area. For example, many cities in Brazil have successfully relied on participation of residents and neighborhoods for setting their municipal and district budgets since the 1990s. Or to take another example, India passed a ‘Right to Information Act’ in 2005, which subsequently led to the creation of hundreds of thousands of social audit and oversight committees pushing for public accountability across the country. These committees are recognized by the state in order to improve local administrative performance.

There is not the slightest doubt that initiatives and popular committees since the beginning of the revolution on the 25th of January, 2011 have made great strides in shifting community-driven projects from a charitable or philanthropic framework to a citizen-led, socially-conscious development model based on the full exercise of citizenship. We can consider the role played by these committees as an alternative to the LPCs which were corrupt and subject to partisan and political exploitation that took place at the expense of citizens’ interests and rights. However elected LPCs will one day return. Their return may lead to an erosion of legitimacy for direct, popular action. However, this need not be the case. Through a collaborative effort and a shared vision, these popular initiatives are the best chance to make a fundamental, sustainable change in the system of local administration in Egypt.

Comments